Baroque, Concerto, Works

Many of Bach’s cantatas and oratorios include instrumental sections, such as sinfonias or overtures, which are musical masterpieces in their own right. Bach freely interchanged his compositions as he saw fit, borrowing from his instrumental works as needed to fill out his vocal works, and vice versa.

This Concerto in D major is based on the first three movements of the Easter Oratorio, which according to musicological research may well have been performed separately as a three-movement instrumental concerto.

The first two movements (Allegro and Adagio) are taken verbatim from the Oratorio. The third movement is based on the Oratorio’s following choral number, with the original orchestral opening and accompaniment, and vocal lines arranged for instruments. The first and third movements of this concerto are scored for a large orchestra of trumpets, timpani, oboes, bassoon, strings and continuo. Majestic openings contrast with more quiet, introspective sections, including a section featuring solo violin in the first movement and a section with a small violin-oboe-continuo chamber ensemble in the third movement.

The second-movement Adagio is a mellifluous oboe solo over string accompaniment, serving as an introspective contrast to the exuberant outer movements.

Baroque, Suite, Works

The Bach family of central Germany was prolific, producing generations of musicians from the 16th through the 19th centuries. While its greatest exemplar was undoubtedly Johann Sebastian Bach, many other Bach family members achieved local and international renown as instrumentalists and composers.

One of these was Johann Bernhard Bach, who was Johann Sebastian’s cousin and contemporary. He studied organ with his father (Johann Aegidius Bach) and then took up successive posts as organist and harpsichordist in Erfurt, Magdeburg and Eisenach, where he worked from 1703 until his death in 1749.

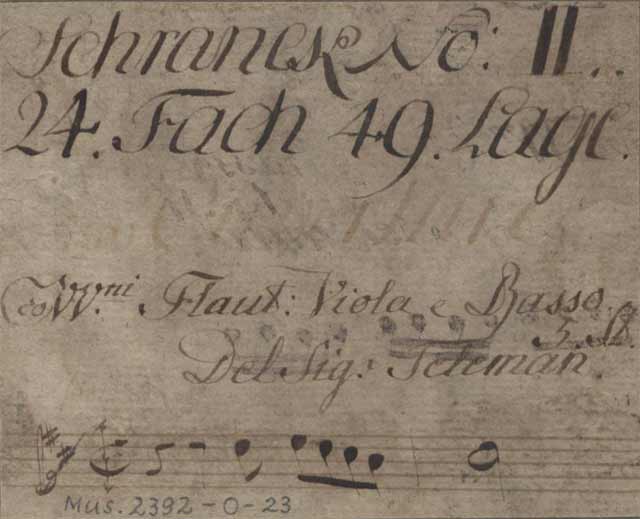

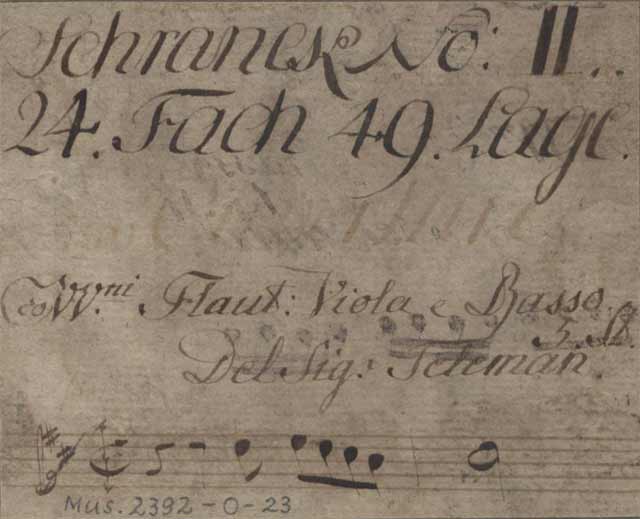

Besides his instrumental talents, Johann Bernhard was also a gifted composer. While little of his work has survived, the works that have come down to us include four orchestral suites. The suites show Georg Philipp Telemann’s influence (as was remarked by contemporaries); Johann Bernhard probably became acquainted with Telemann in Eisenach (where Telemann also worked from 1706-1712). Of interest, Johann Sebastian so esteemed his cousin’s suites that he was involved in copying them for his own use (which is how they were preserved).

The G major suite we are playing today is scored for strings and continuo, to which we have added oboes and bassoons as was often done at the time. The work opens with an “overture” in French style, with stately and sprightly sections. After that there are six contrasting movements based on stylized French dances, which alternately convey elegance, gaiety, introspection and joy.

Baroque, Suite, Works

This is one of Bach’s best-known works for large orchestral ensemble. It was probably composed in the 1720s originally as a suite for strings and oboes, to which trumpets and timpani were later added.

It is a work in 5 movements, made up of an Overture (prelude), Air, and three dance movements (Gavottes I & II, Bourée and Gigue). The opening movement is a “slow-fast-slow” Overture in highly formalized French baroque style, made more brilliant by the use of trumpets and timpani. This is followed by a sprightly section in fugal style, which includes chamber-music like interludes featuring single strings and winds, after which the movement reverts back to the slow opening style.

The heart of this suite is the second movement Air (popularly known as the “Air on the G string,” even though it is certainly not played all on that string!). The Air is both tender and atmospheric. It is grounded on a “walking” ‘cello-bass line, and features an interplay among the first violin melody line and motifs brought out by the second violins and violas.

While the dance movements which follow the Air are more typical of the traditional suite style, Bach uses trumpets and timpani for additional instrumental color and highlights. The two Gavottes are paired 4/4 dance movements, with Gavotte II featuring contrasting loud and soft sections. They are followed by a fast Bourée. The suite ends with the closing Gigue, with trumpet and string passages evoking hunting calls.

Baroque, Concerto, Works

The collection of 12 concertos known as “L’Estro Armonico” (Harmonic Inspiration) was first published in 1711 in Amsterdam. It includes some of Vivaldi’s most famous concerti, known to beginning violin students and professionals alike.

The collection itself is divided into 4 groups of three concertos apiece; each group consists of a solo, double and quadruple concerto. Concerto No. 10 is one of the quadruple concertos. The soloists are many – 4 solo violins, solo violoncello, and a number of solo viola parts (plus orchestra and continuo).

The concerto is basically a three-movement (fast-slow-fast) work, although the slow movement is itself divided into smaller segments. Vivaldi gives each of the soloists his/her own lines and motifs, with plenty of inventive interplay.

Baroque, Suite, Works

During his long and productive life (1681-1767), Telemann became one of the most celebrated of baroque composers. His output was vast, ranging from operas and cantatas to concertos and intimate chamber works.

One of his most charming pieces is the programmatic Don Quixote suite for strings and continuo. The suite opens conventionally enough, with a formal French-style baroque overture. The movements which follow, however, depict different scenes from the adventures of Don Quixote, Cervantes’ famous knight, and his squire, Sancho Panza.

It begins with the “Awakening of Don Quixote,” with string drones evoking sleep, followed immediately by the “attack on the Windmills,” with furiously rushing string passages. “Sighs for Princess Aline” features accented descending eighth notes characteristic of 18th-century passages evoking “tender” emotions. “Sancho Panza Swindled” has a rough peasant atmosphere, depicting the squire being tossed in a blanket. “Rosinante Galloping” evokes the smooth stride of Don Quixote’s horse, while “The Gallop of Sancho Panza’s Mule” shows the ungainly “start-stop” step of the squire’s transport. The Suite closes with “Don Quixote at Rest,” also featuring string drones.

Baroque, Concerto, Works

Bach was a versatile composer. He reworked many of his instrumental concerti for harpsichord, and vice-versa (the two violin concerti, Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 and this concerto for oboe and violin are notable examples).

After considerable research, this three-movement work was reconstructed from Bach’s concerto for two harpsichords in C minor, the original violin-oboe version having been lost.

The first movement opens with an eighth-note theme with stated by the orchestra and answered by the violin and oboe. While the solo lines are prominent, they are interwoven with the orchestra, including delicate contrapuntal textures. The second movement is a lovely duet, with spun-out solo melodies juxtaposed against a muted, mostly plucked orchestral accompaniment. The vigorous last movement features sharp dynamic contrasts and florid solo passages before its resounding end.

Baroque, Suite, Works

The life of William Boyce (1711-1779) spanned the flowering of the baroque era through early classicism. Boyce was active in official London music circles, becoming Composer to the Chapel Royal in 1736 and Master of the King’s Musick in 1755.

He composed a number of symphonies, concerti grossi and overtures for various combinations of strings and winds (although his best-known work is the song “Heart of Oak” which he wrote for a theatrical pantomime).

He published his twelve overtures in 1770, still mostly in high baroque style. They are based largely on celebratory Odes for royal birthdays which Boyce was required to write as part of his official duties.

Overture No. 11 is based on the 1766 Birthday Ode and features strings, oboes, bassoon, trumpets and timpani. The trumpets and timpani play a prominent role, particularly in the formal introduction and the fugue which follows.

Baroque, Suite, Works

When Charles II mounted the throne in 1660, one of his first acts was to lift the ban on theatrical performances, imposed by the Puritans during the Commonwealth years after the Civil War of 1642. Very soon, the ‘masque’ entertainment, involving music, spectacle, dance and drama, was again a thriving business.

Indeed, Purcell himself wrote incidental music (‘incidental’ as it was not part of the action, but occurred in the intermissions and interludes) for 43 plays in all. Several of these were preserved in the Orpheus Britannicus collection, thanks to which we still have many of these wonderful pieces today.

Although the original play of 1690 is now lost, these lovely dance movements remain, here orchestrated by another great English composer, Gustav Holst. They all display Purcell’s delight in harmonic pungency, wonderfully independent contrapuntal writing and endless inventiveness (the Jig is actually an ingenious arrangement of the popular tune Lilliburlero, with the melody in the bass).

Baroque, Concerto, Works

Baroque, Cantatas, Works

Bach composed this cantata in Leipzig in 1724 “for the 14th Sunday after Trinity.”

The cantata is in seven parts. It opens with a majestic chorus based upon a chromatic descending bass line. The choral passages are an interplay between the alto, tenor and bass lines, with the sopranos joining in with the choral melody. The initial orchestral motif is in turn taken up by the chorus; other themes that Bach first gives to the chorus are then taken up by the strings and winds. T

he following movement is a soprano-alto aria (sung today by the women’s chorus), the text beseeching help from above and the music charming in its dance-like motifs. Tenor and bass recitatives and arias follow, with initial forebodings ending in religious affirmations. The closing chorale ends this work on a note of hope.