Classical, Concerto, Works

Czech composer Johann Baptist Vanhal (or Wanhal) lived from 1739 to 1813. He was born in Nechanice, Bohemia, and died in Vienna, where he spent most of his life. Vanhal was well-known among the Viennese composers of his era, and his music was respected by Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven. He was a prolific composer, with 100 string quartets, at least 73 symphonies, 95 sacred works, and a large number of instrumental and vocal works attributed to him. He was also an accomplished instrumentalist, and on a memorable occasion in 1784 played string quartets with Haydn, Dittersdorf, and Mozart.

Vanhal’s bass concerto is one of the best-known Viennese concerti for this instrument and is in the tradition of other works for bass composed by Dittersdorf, Hoffmeister, Pichl and Sperger. While the exact date of its composition is not known, it was possibly written in 1773. The orchestral parts were preserved in manuscript form by Johann-Matthias Sperger, a pre-eminent Viennese bass soloist.

The concerto is in a typical three-movement form, written in classical style. The movements consist of an opening allegro moderato, in sonata form; a second movement adagio, with extended lyrical bass melodies; and a lively allegro in rondo form, featuring elegant solo passagework. In all three movements the solo bass music is virtuosic, exploring its tonal possibilities and spanning the entire range of the instrument.

Current Season, Romantic, Suite, Works

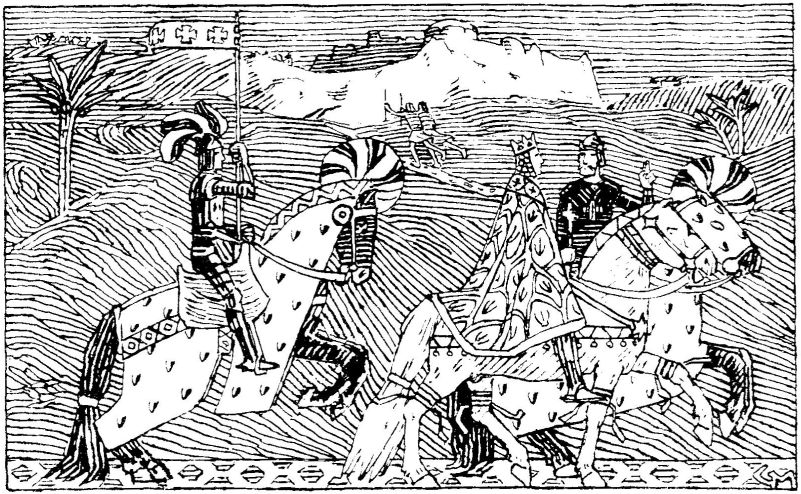

Grieg initially composed an eight-piece set of incidental music for a historical play written by his friend Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson. It was published as Op. 22 and first performed in Christiania in 1872. The play itself was based on the life of Sigurd Jorsalfar (“Sigurd the Crusader”), a king who ruled Norway from 1103-1130 and went on a crusade to Jerusalem. The plot focuses on the tensions between Sigurd and his brother/co-ruler Eystejn; a love-triangle of the brothers with Borghild; and the brothers’ reconciliation. In later years Grieg compiled a 3-movement orchestral suite based on the original incidental music. He published it as Op. 56, and it was premiered in Oslo in 1892.

The opening prelude, “In the King’s Hall,” is a graceful march, first stated in the winds and then taken up by the entire orchestra. A contrasting lyrical section featuring woodwinds leads to a reprise of the opening section. The Intermezzo (“Borghild’s Dream”) is dark and mysterious, with a contrasting agitated section punctuated by string and wind outbursts. The final “Homage March,” originally meant to signify the brothers’ reconciliation, opens with brass fanfares. The main martial theme is played first by four solo ‘cellos, and then broadened to include strings, solo winds, and brass. A contrasting middle section is introduced by percussion and harp and features the strings. The martial theme is repeated by the orchestra to end the Suite.

Classical, Current Season, Symphony, Works

After the death of his long-time patron, Prince Nikolaus Esterhazy, Haydn was engaged by the impresario and violinist J. P. Salomon to travel to London in 1791. In return for generous financial terms, Haydn agreed to write operas, symphonies and numerous other pieces for Salomon’s concerts. Haydn so won over London society that he was invited back for a second trip, in 1794. A major attraction of these concerts were Haydn’s celebrated “London Symphonies” (nos. 93-104), which he composed between 1791 and 1795.

Symphony No. 97 was first performed in 1792, at the Hanover Square Rooms in London. A four-movement work, it is full of Haydn’s humor, wit and special effects. Opening with a majestic (though tonally unsettled) Adagio, the following Vivace is built on a powerful C-major descending triad. The contrasting second theme has a folk-tune flavor, full of graceful flourishes. The Adagio Ma Non Troppo is based on a theme and variations, giving prominence to each of the orchestra’s sections, with a contrasting F minor section in the middle. The Menuetto and Trio are fully written out to showcase the musical themes with different orchestrations. In a nod to Salomon, Haydn gave him a violin solo in the last 8 bars of the trio, played an octave higher than the other violins! The final Presto Assai is a sparkling rondo, with unexpected key changes and rhythmic surprises to the very end.

20th Century, Concerto, Works

Shostakovich wrote the work for his friend Mstislav Rostropovich, who committed it to memory in four days and gave the premiere on October 4, 1959, with Yevgeny Mravinsky conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra in the Large Hall of the Leningrad Conservatory. — Wikipedia

Concerto, Romantic, Works

Dvořák composed his violin concerto, a masterpiece of the romantic concerto literature, in 1879. He was inspired to write it after meeting the great violinist Joseph Joachim, to whom he had been introduced by Johannes Brahms. Dvořák sent the initial manuscript to Joachim, who suggested a number of changes to it, particularly in the solo part, and Dvořák subsequently revised it. However, Joachim never performed the concerto, possibly on account of its unorthodox structure. After a number of other revisions, the concerto was premiered in Prague in 1883, with the noted young Czech violin virtuoso František Ondříček as the soloist.

With lush melodies and allusions to Czech folk tunes, the violin concerto fits squarely into Dvořák’s “Slavic” period, during which he composed works such as his 6th Symphony, the Czech Suite, the first set of Slavonic Dances, the E-flat Major String Quartet Op. 51, and the A-Major String Sextet Op. 48.

The concerto is a three-movement work, albeit with some unusual features. It opens with a vigorous orchestral “foreshadowing” theme in A minor; the passionate main theme is introduced by the solo violin a few bars later. A gentle second theme in C Major appears in the middle of the movement. The music then becomes more free-form, taking on an almost a rhapsodic quality. After a restatement of the opening theme, instead of a full recapitulation there is a short transition section featuring solo violin and woodwinds, and the music then moves without a break into the second movement.

The lyrical Adagio is an extended meditation on a free-flowing theme. It is interrupted several times by an abrupt dialogue between the solo violin and horns, later taken up by the full orchestra. The end of the movement features a novel duet between the solo violin and horns before ending in a reverent hush.

The lilting third movement is full of folk-theme references. It opens with an uplifting theme based on the furiant, a spritely Czech dance. In the middle of the movement, a slower section based on the Czech dumka makes its appearance. A final statement of the opening furiant brings the concerto to a joyous close.

Romantic, Tone Poem, Works

Mahler composed this intense and dramatic piece in 1888, just after he had finished composing his Symphony No. 1 (the “Titan”). Originally composed as a tone poem, Mahler incorporated it, with a number of changes, seven years later into his massive Second Symphony (the “Resurrection”). Mahler himself, a noted conductor as well as composer, performed “Totenfeier” as a standalone piece in a number of concerts, even after finishing his Second Symphony.

A number of Mahler’s writings indicate that he thought of this work as the finale to his first symphony — that he was in fact burying the hero of the “Titan.” The tone poem is structured as a funeral march, but is also interspersed with ethereal interludes and themes of menace and terror. In the middle of the movement, the brass section introduces the “Dies Irae”, a medieval Latin hymn referring to Judgment Day. Of note, Mahler did write program notes for his Second Symphony in 1901, but later withdrew them from publication. They nonetheless open a window for us into his thinking. Here is how he described “Totenfeier:”

We are standing at the coffin of a well-loved man. His life, struggles, suffering, and passions pass by our mind’s eye for the last time. — And now, in this solemn and most shattering moment, when the confusions and distractions of everyday life are stripped away, a terrible grim voice, which we usually ignore in life’s daily hustle and bustle, grips at our heart: Now what? What is this life — and this death? Does it continue for us? Is it all just an empty dream, or does this life and this death have a purpose? — And we must answer this question, if we are to continue living.

Classical, Overture, Works

The 25-year old Mozart composed his comic opera, The Abduction from the Seraglio, in 1781-2, shortly after his move from Salzburg to Vienna. The opera is set in a Turkish harem. Belmonte, a Spanish nobleman, seeks to free his fianceé, Konstanze, and their servants from the harem where they are imprisoned after having been captured by pirates and sold into slavery. In keeping with the opera’s oriental theme, Mozart added a number of “Turkish-style” instruments to the orchestra — bass drum, cymbals, triangle and piccolo. The Overture is witty and sparkling, with alternating loud and soft passages and a short reflective interlude in the middle.

20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, With Audio, Works

Born in late 19th-century Russia,

Rachmaninoff was one of the last great Romantic composers. An accomplished composer, pianist and conductor, he was born into a musical family and began piano lessons at age 4. After graduating from conservatory, he became well known for his piano works and symphonic compositions, and made his conducting debut in 1897. He left Russia in 1917 after the Russian Revolution, and eventually made his way to the United States, where he focused on a career as a pianist. In the 1930s he lived for a time in Switzerland, where he composed the

Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini in 1934. The Rhapsody quickly became a concert staple and is today one of his best-known works.

Although titled a “Rhapsody”, this work is actually a set of variations for solo piano and orchestra. It is based on a theme composed by Niccolò Paganini, the great 19th-century Italian violin virtuoso, in his 24th Caprice for solo violin. The Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini consists of 24 separate, highly diverse variations, each based on Paganini’s original theme, with close collaboration between the soloist and orchestra. For the solo pianist, the Rhapsody is an extraordinary tour-de-force, with technical demands intermixed with delicate passagework, cadenzas and ultimate Romantic lyricism.

The work can be divided into several broad sections: an opening fast section (Introduction and Variations I-V); a more free-form “rhapsodic” section (Variations VI-XI); a minuet and scherzando section (Variations XII-XV); a slow section, including the emotional heart of the work (Variations XVI-XVIII); and a rousing finale (Variations XIX-XXIV).

Unconventionally, it does not open with the theme itself, but with a bare harmonic skeleton; the theme itself appears in Variation II, appropriately introduced by the violins. In Variation VII, Rachmaninoff introduces a notable counter-theme based on the Dies Irae, a medieval Latin hymn referring to Judgment Day, and a tune with which Rachmaninoff had a life-long fascination. Probably the best known part of the Rhapsody is Variation XVIII, with its lush romantic theme played first by the solo pianist, and taken up in turn by the orchestra. The last section of the Rhapsody is a driving accelerando and ends, after a forceful reprise of the Dies Irae, with a witty pianistic flourish.

Romantic, Tone Poem, With Audio, Works

Borodin composed

In The Steppes of Central Asia in 1880 as part of a production to commemorate the Silver Jubilee of Tsar Alexander II, who had been instrumental in expanding the Russian Empire into Asia. While the production itself never took place, Borodin’s piece was premiered in 1880 under the baton of Rimsky-Korsakov and has been immensely popular ever since. Borodin himself provided the following programmatic description in a note to the score:

In the silence of the sandy steppes of Central Asia, the sounds of an unfamiliar peaceful Russian song are heard. In the distance we also hear the melancholy sounds of an oriental melody, and the steps of approaching horses and camels; a caravan approaches. Under the protection of Russian soldiers, the caravan continues its long journey securely and without fear on its way through the immense desert. The Russian and Asiatic melodies join in a common harmony; their refrains continue to be heard for a long time before finally dying away in the distance.

Romantic, Suite, Works

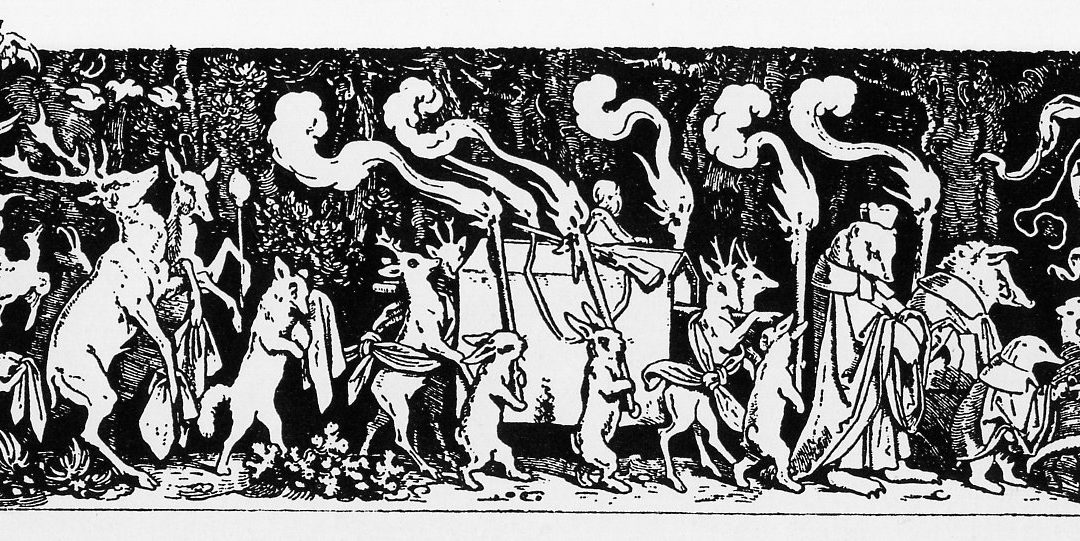

Mussorgsky was a member of an influential group of Russian composers known as “The Five” – Mily Balakirev, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Borodin. Together they forged a uniquely Russian musical style based on the country’s folklore and history. Mussorgsky himself composed numerous works for piano, orchestra, opera and voice. Among his best-known works are the opera Boris Godunov, the orchestral tone poem Night on Bald Mountain, and the piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition.

The piano suite was composed in 1874 and was based on a series of drawings and paintings by the Russian artist Viktor Hartmann. It proved so popular that numerous arrangements have been made of it (the Ravel orchestration done in 1922 is the best-known of these). The first orchestration of Pictures at an Exhibition, which we are performing at this concert, was prepared in 1886 by Mikhail Tushmalov, a pupil of Rimsky-Korsakov. Rimsky himself oversaw the editing of the score and conducted the première, in 1891.

This orchestral arrangement contains most of the original movements of the piano suite. After the opening Promenade, the mood shifts to the “Old Castle,” with haunting melodies introduced by bass clarinet and English horn. Next is the spritely “Ballet of the Chicks in their Shells” featuring strings and woodwinds; “Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle” is a ponderous dialogue between two Polish Jews, one rich and the other poor. “Market at Limoges” depicts women arguing furiously in a small French town marketplace. The tone shifts abruptly in “Catacombs;” punctuated by sudden brass chords, it is based on a painting in which Hartmann is examining the famous underground catacombs of Paris by lantern light. In the following “Con mortuis in lingua mortua,” the opening “Promenade” theme is eerily reprised in a minor key. The “Hut on Hen’s Legs” is based on a Hartmann drawing of a clock in the form of a witch’s hut; Mussorgsky puts the focus on the witch’s flight, with dramatic scales and passages in thirds.

It leads directly to the grand last movement, “The Great Gate of Kiev”. It is based on Hartmann’s design of a monumental gateway to the city in an ancient massive Russian style, capped with a cupola shaped like a Slavonic helmet. Its familiar grand theme is repeated several times with increasing intensity, interspersed with wind interludes reminiscent of Russian Orthodox chants. It ends in a triumphal paroxysm of massive chords and pealing bells.