20th Century, Symphony, Works

In 1936, after a performance of “Lady MacBeth of the Mtsensk District,” an article in “Pravda,” the Russian newspaper of the time, publically denounced Shostakovich. The article, often attributed to Joseph Stalin, entitled “Muddle or Music,” claimed that Shostakovich had “missed the demands of Soviet Culture to banish crudity and wildness from every corner of Soviet life.” It went on to say, “The danger of this tendency in Soviet music is clear. Leftist ugliness in opera is growing from the same source as leftist ugliness in painting, poetry, pedagogy, and science. Petit bourgeois ‘innovation’ is leading to a gap away from true art, science … literature.”

During this time period in Soviet history, all art was expected to fit within the confines of Socialist Realism. Socialist Realism dictated that everything be in support of Communism. Music and art were to enhance and support the government, not cause tension or spur acts of rebellion.

Shostakovich feared for his life, as artists who flew in the face of social norms often found themselves executed or banished. Perhaps the only thing that saved him was the fact that in the early 1930’s Shostakovich had written a score to a movie entitled “Counter Plan,” which was released for the 15th anniversary of the October Revolution. One song from that score, “The Morning Greets Us,” gained international acclaim and became the first Soviet song to be considered a hit. This is perhaps the only thing that saved Shostakovich from a gruesome fate.

Composed between April and July of 1937, the 5th Symphony was Shostakovich’s response to the events of the year before. Premiered on November 21, 1937, it was received with thunderous applause that lasted more than half an hour.

Shostakovich had no choice but to claim that the piece was nationalistic in nature. In fact, Shostakovich likely viewed the piece as his chance to regain favor with the Communist party. The last movement quotes a song Shostakovich wrote earlier in the 1930’s, based on a poem by Pushkin, which deals with rebirth. Later on in his memoirs, however, he explained that he wrote the piece in direct response to the persecution and oppression that existed under Stalin’s rule. Since the time of its premiere this symphony has become one of the staples of the classical repertoire and is considered one of the greatest works of the 20th century.

As you listen, you will hear moments of terror, pain, pleading, and downright despair; but out of these moments, Shostakovich gives us wonderful glimpses of hope and in the last movement a feel of redemption and even victory.

(Christopher Hisey)

20th Century, Songs, Works

The Four Last Songs were among Richard Strauss’ last works. He composed them in 1948, shortly before his death. They are all set to poems, three of them by Hermann Hesse — Frühling (Spring), September, and Beim Schlafengehen (While Falling Asleep) — and one of them by Joseph von Eichendorff — Im Abendrot (At Twilight). These were not initially conceived of as a set of songs, but published in that form after his death and premiered in 1950.

The words and music are calm and contemplative; the last three songs evoke an acceptance of death. The music features melodic interplays between the soprano and the orchestra, subtle chromatic shifts, and lyrical horn passages.

(M. F. Tietz)

Baroque, Opera, Works

A dramatic work for three voices and orchestra.

Classical, Symphony, Works

One of the more frequently performed early symphonies of Mozart.

Romantic, Tone Poem, Works

Wagner’s work for chamber orchestra was composed as a birthday present to his wife Cosima.

20th Century, Concerto, Works

This concerto was dedicated to Marcel Moyse.

20th Century, Concerto, Works

Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992) was one of Argentina’s most gifted and prolific composers. He started out as a self-taught composer and accomplished player on the bandoneon, an Argentine variant of the concertina/accordion. After formal composition study in Paris he returned to Argentina and revived tango in a modern “nuevo tango” form.

He wrote the four movements of the Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas (Four Seasons of Buenos Aires) between 1965 and 1970 for his tango instrumental quintet (violin, piano, electric guitar, bass and bandoneon). They were conceived as separate pieces, although Piazzolla occasionally performed them together.

In the 1990s, violinist Gidon Kremer commissioned the Russian composer Leonid Desyatnikov to arrange these four compositions for solo violin and string orchestra. Otoño Porteño is the third of these. It is characterized by brilliant passages for the solo violin, strong pulsing rhythms/syncopation, and wistful slow interludes for solo ‘cello and solo violin.

Baroque, Concerto, Works

Vivaldi composed “Le Quattro Staggioni” (the Four Seasons) in 1725. The “Seasons” consist of four programmatic concerti for solo violin and orchestra, of which L’Autunno (Autumn) is the third.

Vivaldi wrote descriptive Sonnets for each of the concerti, with indications of how they should be performed.

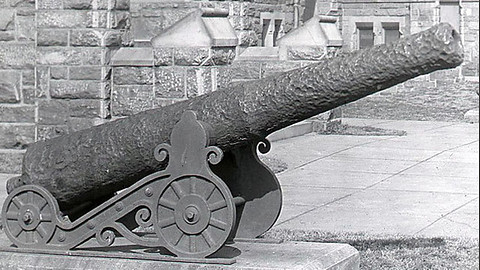

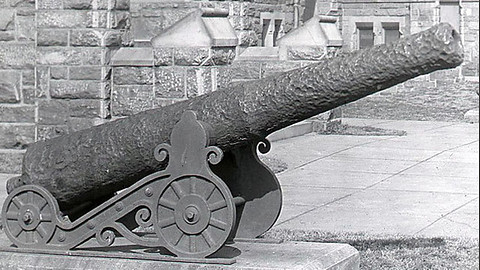

L’Autunno opens with peasants celebrating the harvest with song and dance. They start drinking wine, become progressively more tipsy, and finally fall asleep. In the hushed second movement, the pleasant temperature causes everyone to abandon singing and dancing, and invites many to enjoy the sweetness of sleep. The last movement describes a hunt, complete with mounted hunters, hunting horns, guns, hounds, and their quarry.

20th Century, Suite, Works

This work began as a film score. In 1934 Prokofiev was commissioned to compose a score for Lieutenant Kijé (in Russian, Parootchik Kizhe), a movie satirizing the military and bureaucracy in Czarist Russia.

The plot is based on a mythical tale that hinges on a spelling error. In the film, a clerk misspells a phrase while copying out military orders: the Russian phrase “parootchiki, zheh” (“the lieutenants, however…”) becomes “Parootchik Kizheh (“Lieutenant Kizheh”). The Czar reads the orders and thinks there is a “Lieutenant Kijé” in his guard company!

Not daring to tell the Czar about the copying mistake, the Czar’s aides, courtiers and military officers instead fabricate an entire life for the “Lieutenant.” Besides a military career, they concoct a romance and even a marriage for him.

The fictional lieutenant rises high in the Czar’s esteem and is rewarded with promotions and riches. Finally, the Czar’s aides devise a way to “kill off” the non-existent lieutenant, and he is buried with military honors.

By 1937 Prokofiev reworked the movie score into a substantial five-movement suite, each depicting a scene from the fictional lieutenant’s life. It begins with the “Birth” of Kijé, featuring a far-off trumpet solo and martial music.

This is followed in succession by a Romance based on a love song (featuring a double bass solo); Kijé ‘s marriage, with a flourish of brass, pomp and ceremony, followed by a lively trumpet tune; the famous Troika, evoking a winter sleigh ride in the snow; and, finally, Kijé ‘s death and burial, in which brief passages from the other movements serve as reminiscences of his fictional “life.”

The suite ends as it began, with a trumpet solo in the distance.

20th Century, Suite, Works

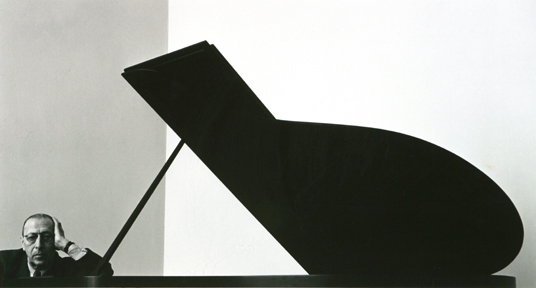

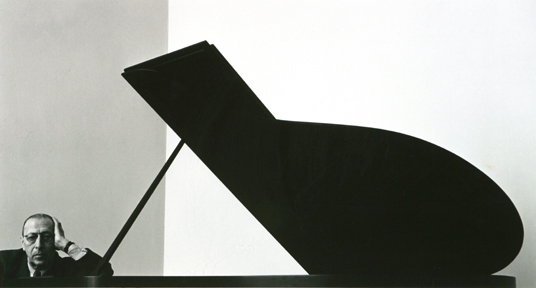

Stravinsky orchestrated this suite for small orchestra based on simple tunes he initially composed for the piano between 1914 and 1917. It is one of many “miniature” works that Stravinsky composed during his life, experimenting with various combinations of instruments, styles and textures.

This short work is in four movements — an opening calm Andante; the rollicking “Napolitana,” evoking an Italian street song and featuring woodwinds; an intense Española, with jagged rhythms, offbeats and contrasts; and the final Balalaȉka, tuneful throughout, with an abrupt ending.