Concerto, Romantic, Works

The years from 1720 to 1750 were, from the perspective of the present, dominated by Johann Sebastian Bach; but for a musically aware person of the period Georg Philipp Telemann was the foremost musician of his day. His music, while firmly rooted in the contrapuntal intricacies of the Baroque style, served as a bridge between the old methods and the emerging Classical style of simple textures, clear harmonies, and elegant melodies.

Telemann founded the first series of public concerts, taking music from the spheres of court, church and opera house into the realm of audiences who wished to gather simply for the pleasure of listening. He saw that instrumental music in these other spheres was merely an adjunct to ceremony, contemplation or amusement, and that music could and should be appreciated as an abstract art, unadorned, and not subservient to other goals. His insight revealed a path that composers, performers, and audiences have trod ever since, leading directly to our concert today.

Although Telemann was the most prolific of 18th-century composers (a period when prolific composers abounded), he still found time to travel frequently and widely across Europe, absorbing musical influences from a wide variety of composers and nationalities. The “Concerto Polonois” was a result of a visit to Cracow, Poland, and it incorporates characteristic elements of Polish folk dance and presents them in the new compositional style.

20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, Works

Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992) was one of Argentina’s most gifted and prolific composers. He was a self-taught composer and an accomplished player on the bandoneon, the Argentine version of the accordion. Piazzolla is inextricably associated with the tango, which he was largely responsible for re-energizing and modernizing in his numerous compositions.

In his Histoire du Tango, Piazzolla sought to trace the evolution of the tango itself from an erotic, “not quite respectable” dance to its modern form, which is still very much alive and well in today’s Buenos Aires.

The Histoire is a series of four pieces – “Bordel 1900, Café 1930, Nightclub 1960, and Concert d’aujourd’hui” – which he composed originally for flute and guitar. We are performing the third piece in this series, in an arrangement for soprano saxophone and orchestra by Mark Spede.

Like all tangos, the music is full of wistful melody, with abrupt rhythms alternating with hints of sadness and languor.

20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, Works

Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) was one of France’s most intriguing 20th-century composers. After studying at the Paris Conservatoire, he secured a position in 1917 as a cultural attaché at the French Embassy in Brazil, where he received much exposure to Brazilian music. Upon returning to Paris in 1919, he became associated with the circle of famous early 20th-Century French composers known as “Les Six.”

The author of numerous symphonic and chamber works, Milhaud originally composed the music for Scaramouche in 1937 as incidental music for saxophone to accompany a children’s play. He was then asked to transcribe the music for two pianos, which he did as a three-movement suite. The transcription proved so popular that he then re-orchestrated the suite for saxophone and orchestra in 1940, when it was premiered by the famous French saxophonist Marcel Mule.

The music is in three movements – Vif , Modéré, and Brazileira. The first movement is a witty dialogue between the solo saxophone and orchestra, with some motifs loosely based on an English folk song. The second movement is more reflective, with the soloist initially juxtaposed against a sonorous muted chorus of trumpets, trombones, bassoons and basses. The last movement, based on samba rhythms, is one of his most recognizable works and clearly shows the influence of his early Brazilian interlude.

Classical, Solo with Orchestra, Works

This is one of 6 famous concertini originally attributed to the Italian composer Pergolesi. These works were first published in Holland in 1740, but without mention of a composer. Recent scholarship has discovered that all of these works, far from being the work of an Italian, were actually composed by a Dutch nobleman, Unico Wilhelem Graf Van Wassenaer. He had permitted his court violinist, Carlo Ricciotti, to publish them, but only on condition that he (Van Wassenaer) was not associated with them. (Perhaps he did not wish his noble reputation to suffer by being so closely associated with the music profession.)

This concertino, like all of the others, is Italianate in style, with richly worked-out counterpoint and lush 7-part string writing (including 4 separate violin parts in Neapolitan style). The movements are alternately slow and fast, with a stately introduction, a fast alla breve second movement, followed by a slow third movement in “sicilienne” style.

Stravinsky adapted the last movement, in fast 6/8 time, as the basis for the “Tarantella” movement in his Pulcinella Suite.

Concerto, Romantic, Works

Schumann composed the ‘cello concerto in 1850, just before his third symphony and six years before his untimely death.

He styled it as a “Concert piece for ‘cello with orchestral accompaniment.” It is a three-movement work, although all of the movements are connected and played without break.

After three wind chords, the ‘cello opens with a soaring song-like melody, later echoed by the French Horn and by the winds after the slow movement. The short slow movement is a languorous interlude, featuring a simple solo melody accompanied by a solo orchestral ‘cello, string pizzicati and wind echoes. After a brief transition, with an evocation of the slow movement, the solo ‘cello leads into the quick last movement, which is characterized by a leaping two-note theme followed by rising sixteenth notes. The last-movement cadenza leads inexorably to a fast and joyous conclusion.

20th Century, Occasional Piece, Works

This short piece can perhaps best be described as an impressionist miniature jewel, more evocative of mood than anything else. Curiously, the title has no particular significance; Ravel used it because he liked the sound of it.

The Pavane opens with a soaring theme played by the French Horn, picked up later by the winds and finally the muted strings. A contrasting middle section introduced by the flute separates the main thematic material. Impressionist harmonies, muted strings and harp glissandi all combine to evoke shifting moods – first stately and somber, then urgent and lively, and (at the end) wistful and introspective.

20th Century, Suite, Works

Appalachian Spring is undoubtedly one of Copland’s best-known works. It led to his receiving the Pulitzer Prize for music in 1945 and helped catapult him to popular fame.

Copland received a commission to compose the original version in 1943-44 as ballet music for Martha Graham, whose dance company premiered the work in 1944. He originally scored it for 13 instruments and called the piece “Ballet for Martha;” it was she, in fact, who gave it the title “Appalachian Spring” by which we now know it. In 1945 Copland revised the ballet into the full orchestral suite which we are performing today.

A programmatic piece, it describes a scene in Western Pennsylvania in the 1830s centering on a celebration around a pioneer family’s new farmhouse. It opens with a slow introduction to the characters, setting a serene, calm mood with echoing three-note rising themes in the winds. It abruptly shifts to a fast, lively section (opening with leaping octaves in the upper strings), with elated and religious thematic overtones brought out by the brass and winds. This is followed by a slow dance between the bride and her intended groom, full of tenderness and passion. Next, a revivalist and his flock appear; the music reflects folk themes and evokes square dances and country fiddles. A lively solo bride’s dance comes next, heralded by fast scale-like passages in the flutes and violins and then by the entire orchestra.

After a transition which echoes the opening themes, there follow a series of scenes of daily life with a theme and variations based on the Shaker melody “Simple Gifts.” After an inspiring climax, the strings and winds revert to quiet passages evoking contemplation and prayer. At the end of the piece, the pioneer couple are left “quiet and strong” in their new house.

Baroque, Concerto, Works

Bach was a versatile composer. He reworked many of his instrumental concerti for harpsichord, and vice-versa (the two violin concerti, Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 and this concerto for oboe and violin are notable examples).

After considerable research, this three-movement work was reconstructed from Bach’s concerto for two harpsichords in C minor, the original violin-oboe version having been lost.

The first movement opens with an eighth-note theme with stated by the orchestra and answered by the violin and oboe. While the solo lines are prominent, they are interwoven with the orchestra, including delicate contrapuntal textures. The second movement is a lovely duet, with spun-out solo melodies juxtaposed against a muted, mostly plucked orchestral accompaniment. The vigorous last movement features sharp dynamic contrasts and florid solo passages before its resounding end.

Classical, Symphony, Works

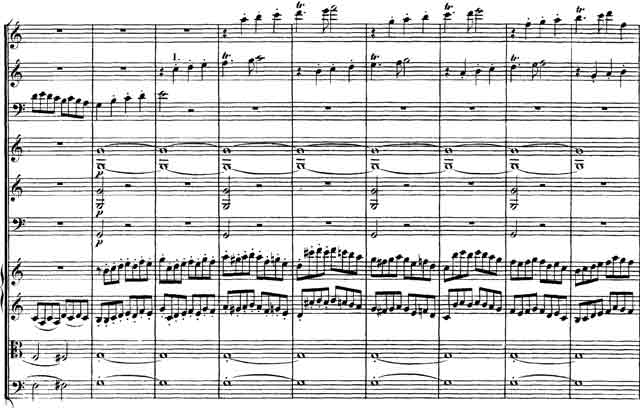

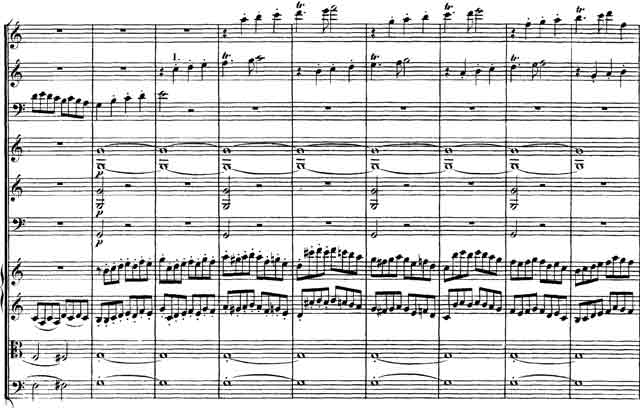

In an astonishing burst of energy, Mozart composed his last 3 symphonies (Nos. 39, 40 and 41) in 1788 in a space of just six weeks.

The last of these three, the “Jupiter,” is grand and majestic in style. Written in C Major, it is complex in structure and form, as well as in its exploration of keys and harmonies. An imposing 5-note initial theme opens the work, setting the stage for rich musical development, alternately elegant and impassioned.

The poignant Andante cantabile opens with a lyrical rising theme by the muted violins. It is taken up in turn by the other instruments and interspersed against running scale-like passages.

After a refined Menuetto and Trio, the magnificent last movement opens with a transparent four-note theme in the violins. From this seemingly simple beginning, other themes are introduced, all of which in turn Mozart weaves into a complex tapestry of musical counterpoint. The total effect is at once grand, elegant, extraordinarily complex, and musically fulfilling.

Opera, Overture, Romantic, Works

La Traviata was first performed in 1853. One of Verdi’s most famous operas, it tells the story of a doomed love affair between a young and beautiful girl of dubious reputation and a young man from the proper social circles. The Prelude to Act III opens with a high ethereal melody played by divided violins. Its foreboding tone and mood set the stage for the opera’s tragic conclusion.