20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, Works

“Tubby,” with music by George Kleinsinger and story by Paul Tripp, was composed in 1946. It serves as a wonderful introduction to the orchestra, and has become a well-loved children’s classic.

It tells the story of Tubby, a fat little tuba who just wants to be treated like all of the other instruments of the orchestra. As the lowest-sounding instrument, Tubby usually just gets to play “oompah-oompah.” What he really wants is to play pretty melodies just like all of the other instruments in the orchestra!

When Tubby first tries to do that, the other instruments make fun of him. After rehearsal, Tubby goes home and sits sadly by a riverbank; but there, he meets a big bullfrog, who teaches him a wonderful new melody. At the next rehearsal, the conductor gives Tubby the chance to play his new melody. Tubby plays it so beautifully that all the other instruments love it and want to play it too!

Everyone joins together in the rousing finale, making Tubby a very happy tuba indeed.

20th Century, Occasional Piece, Works

Voyage is a string-orchestral version of the choral setting of Richard Wilbur’s translation of Baudelaire’s “L’Invitation au Voyage.” The lyrical, seamless vocal lines translated themselves naturally to strings, and the burnished imagery of the poetry finds a happy companion in the richness of the instrumental choir.

20th Century, Works

Perhaps the most famous children’s work ever written, Peter and The Wolf was composed by Sergei Prokofiev in 1936 as a way of introducing children to the instruments of the orchestra.

It opens with Peter, a brave little boy (played by the strings), going out into the meadow and observing a bird (the flute) and a duck (the oboe). The bird and the duck begin talking and then quarreling. A cat (the clarinet) comes along and tries to catch the bird, which flies away. Grandfather (the bassoon) appears and is angry that Peter is in the meadow. It’s dangerous out there; if a wolf should come along, what would Peter do then? Although Peter says he is not afraid, Grandfather takes Peter back home and locks the gate. Sure enough, an enormous wolf (three French horns) suddenly appears; the wolf then chases, catches and swallows the duck.

But Peter, with the help of the bird, manages to trap the wolf with a lasso. The hunters, who had been tracking the wolf, appear and help Peter take the trapped wolf to the zoo. Peter, the hunters, the wolf, grandfather, the cat and the bird then join in the triumphal procession. Even the duck’s quacking is heard, because the wolf had been in such a hurry that he had swallowed the duck alive!

20th Century, Concerto, Works

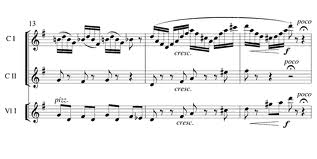

Written in 1954, this short 3-movement work was Vaughan Williams’ last concerto.

It is a compact work, with 2 modernistic outside movements surrounding a slow movement. It begins with a vigorous opening built around rising and falling scale-like passages. This is followed by a second theme (a little reminiscent of Hindemith in style), and a third, folk song-like theme.

The second movement harks back to Vaughan Williams’ earlier melodious and dreamy style. Orchestra and soloist both take part, weaving in and out of the musical fabric; the tuba’s sonorous capabilities are on full display in the scale-based theme followed by baroque-like ornamentation.

The concluding Finale is a rollicking “German rondo” (“Rondo alla Tedesca”), with a robust main theme first played by the tuba and echoed by the orchestra; the second theme is harmonically more adventurous, with a plaintive, almost urgent feel to it. After successive, ever more frenetic renditions of the 2 themes, the concerto ends in a furious dash.

The first and third movements both contain substantial solo cadenzas displaying the tuba’s range and versatility.

20th Century, Solo Vocal, Works

This extraordinary work was composed for tenor Peter Pears and horn player Dennis Brain in 1943. It consists of six songs set to English poems framed by a solo horn prologue and epilogue. While many of the poems deal in some fashion with sleep, decay, or death, each has its own distinct character, beautifully set off by the interplay between the two soloists and the strings.

The Pastoral (“The Day’s grown old”) by Cotton describes a late afternoon scene in the countryside with flocks of sheep, lengthening shadows and sunset. “The splendour falls on castle walls” (“Blow Bugle Blow”) by Tennyson evokes the heroics of a bygone age, with bugle calls echoing and dying in a craggy landscape.

For Blake’s doleful Elegy (on its face, about a rose and its destruction by the worm that finds it), Britten has composed horn and tenor melodies based on minor second motifs. It leads directly into the Dirge, a haunting 15th-century anonymous poem about death and whether salvation or damnation awaits the deceased, depending on his/her conduct in life. The Dirge is also notable for its structure, a multi-voiced fugue played by the strings and horn over an ostinato sung by the tenor.

Ben Jonson’s hymn to Diana the huntress is set as a spritely hunting tune, while Keats’ Sonnet (“O soft embalmer of the night”) is a paean to sleep.

20th Century, Occasional Piece, Works

Sousa reigned as the “March King” in the latter part of the 19th and early part of the 20th centuries. His musical output was prodigious, consisting of marches (well over 100), operettas, suites, songs, arrangements, etc. His “Belle of Chicago” march dates from 1892 and was meant as a tribute to the ladies of the Windy City.

20th Century, Suite, Works

In the early to mid-twentieth century, as the revival of interest in early music continued and intensified, composers explored the possibilities of this music using a modern orchestral sound.

Some of the more notable are the Pulcinella Suite of Stravinsky, the Stokowski Bach transcriptions, the Ricercare from the Musical Offering by Bach/Webern, and the Suite of French Dances arranged by Paul Hindemith.

The Ancient Airs and Dances of Respighi falls into such a category. In each of these composers’ efforts, what is basically an arrangement or transcription of existing earlier music inevitably shows the contemporary stamp of it’s arranger, and the techniques and expression which characterize that particular composer or arranger’s contemporary musical passions as well.

The lute music Respighi used as his source was written for a very quiet and intimate instrument. Respighi manages to find a way to imbue these pieces with his own particular kind of broad orchestral color. Traditional dance forms, in addition to their Italian heritage, also likely appealed to Respighi’s sense of color and variety, lending themselves to the kind of instrumental treatment he used in his own compositions.

20th Century, Suite, Works

Falla was a quintessentially Spanish composer who partially developed his style while living in Paris, between 1907 and 1914. There he became well-acquainted with Ravel, Debussy and Dukas.

He originally composed the music for The Three-Cornered Hat in 1917 to accompany a pantomime based on a story by the late 19th-century Spanish writer Pedro Alarcón. The famous impresario Diaghilev persuaded Falla to turn the music into a full ballet, which was premiered in London in 1919, with sets by Picasso and choreography by Massine. Falla later arranged the music into two separate orchestral suites, the first of which we are performing today.

The story focuses on an ugly and misshapen miller and his beautiful wife, who is very much in love with him; the Corregidor, a local magistrate who wears a large three-cornered hat as a sign of his office; and a series of amorous pursuits and mistaken identities (with a happy ending).

After a short introductory fanfare, the piece opens to an afternoon scene in a small Andalusian village. The miller and his wife, amid their daily tasks, are trying to teach a bird to tell the time; they kiss, then dance.

Announced by the bassoon, the Corregidor appears; he is captivated by the pretty miller’s wife, but leaves the scene after a disapproving glance from his own wife. The miller’s wife dances a rousing Fandango, featuring a typically Spanish meter alternating between 3 and 2.

The Corregidor appears again; the miller’s wife politely curtsies, and then begins a flirtatious dance, teasing the Corregidor with a bunch of grapes which she keeps just out of his reach. The Corregidor stumbles and falls, and storms off. The miller and his wife dance again, reprising the Fandango theme, to end the Suite.

20th Century, Occasional Piece, Works

Ives is one of America’s most intriguing composers. He began his musical studies under his father (a bandmaster), became an organist for a Connecticut church, and began composing around the turn of the 20th century. After graduating in 1908 from Yale University, Ives went into a successful career in the insurance business, but continued his composing activities.

Widely ignored until the end of his life, Ives is now an established American composer. His style is pioneering and eclectic, and runs the gamut from beautiful melody to wild dissonances and polyrhythms.

He wrote his original version of The Unanswered Question around 1906, and revised it between 1930 and 1935. The work is scored for strings, solo trumpet and wind choir (2 flutes, oboe, and clarinet).

While the strings play a slow soft chorale, the solo trumpet asks a series of “questions.” Each time, the wind quartet answers the trumpet. While the first “answers” are slow, they rapidly increase in intensity, tempo and urgency. After a final shrill burst from the winds, the trumpet repeats the question, letting it hang in the air until the end of the piece.

20th Century, Suite, Works

Ravel first composed Tombeau as a suite for piano in six movements, and then arranged it as a 4-movement suite for orchestra in 1919.

A “tombeau” was, in the French baroque tradition, a composition meant as a memorial, and each movement of Ravel’s Tombeau is dedicated to a friend who perished in World War I.

The reference to “Couperin” evokes one of France’s great baroque composers, and indeed the four movements of this work are based largely on baroque French dance forms. Ravel’s genius is to fuse these baroque frameworks with modern harmonies and instrumentation to create works of atmosphere, charm and grace.

The opening Prélude is a cascade of motifs led by the oboe (which has a virtuosic part in this entire work). The dance movements all have main sections with contrasting interludes. The Forlane is a wistful modern rendering of a stately dance, evolving into ever more unearthly harmonies until its resolution; the Menuet is a charming updating of an old classic; and the Rigaudon, with woodwind and brass highlights, provides a rousing finale.