Concerto, Romantic, Works

This concerto is truly a work of superlatives.

It was the last concerto Beethoven composed, and is seen by some as the end of his “heroic” period. The title “Emperor,” although in common use now, is not Beethoven’s; it became attached to the concerto after Beethoven’s death, in 1827, probably due to the nobility and expansiveness of its themes.

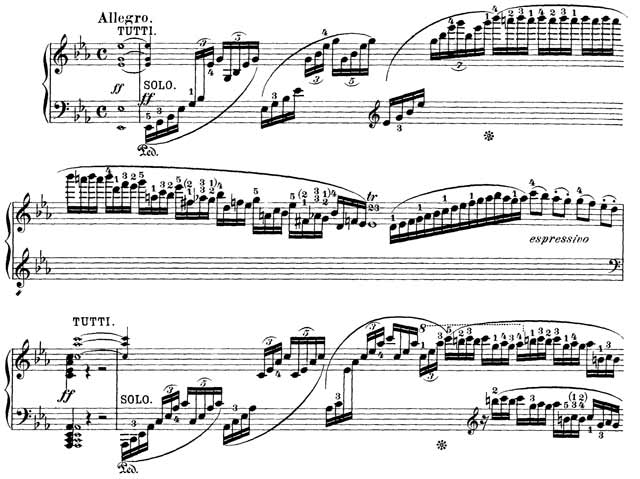

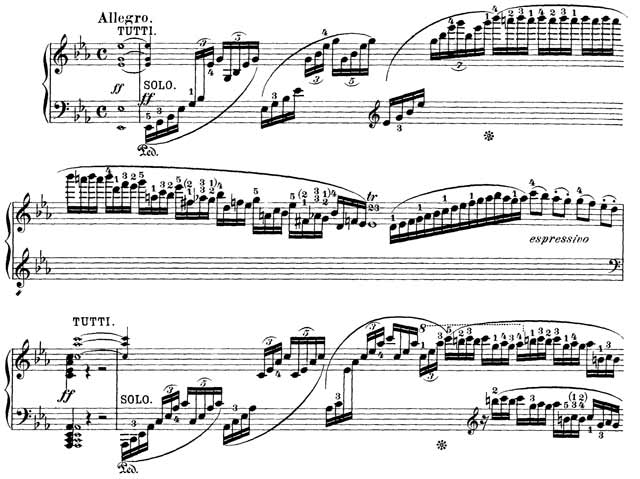

Beethoven composed this work in 1809 during the siege and bombardment of Vienna by the French under Napoleon. Due to his growing deafness, it was the first of his piano concertos where the premiere was played by a pianist other than Beethoven himself (by Friedrich Schneider in Leipzig in 1811, and by his pupil Carl Czerny at the Vienna premiere in 1812). It was also the first concerto in which a composer integrated his cadenzas into the score itself; indeed, it is notable that the piece actually starts with a piano cadenza!

After the opening cadenza, the orchestra states the familiar first martial theme, which includes a turn, descending arpeggio quarter notes, and a dotted eighth-sixteenth-half note motif, all of which make their appearance as subthemes later in the first movement. The second theme also makes its appearance in the opening orchestral tutti, in E-flat minor – a soft step-wise slow “march” immediately reprised in E-flat major as a beautiful melody played by two horns. This basic thematic material is used by Beethoven throughout the first movement, interspersed by richly ornamented piano passages and cadenzas. The key relationships are also notable. Besides the usual familiar keys (E-flat, B-flat, A-flat), Beethoven repeatedly moves into more distant keys, particularly C-flat major/B minor (with a “third” relationship to the concerto’s overall key of E-flat). Also notable are a tendency for themes to move step-wise by a half-tone into different keys.

The following adagio is in B Major (again that “third” relationship). Its opening theme is actually based upon a tune which Beethoven originally intended for a military band (!) and then magically transposed into an ethereal “pilgrim’s song.” After the opening, the theme is repeated twice, once by the piano alone, then by a flute-clarinet-bassoon choir against the piano’s accompaniment.

At the end of the adagio, a step-wise downward movement from the bassoons to the horns brings the tonality back from B major to B-flat (the fifth of E-flat). After a tentative prelude, the pianist launches full throttle into the robust last movement, a classic joyous rondo with hunting theme overtones. The rondo theme is repeated four times, and interspersed with variations by soloist and orchestra. In the coda the piano plays part of the rondo theme accompanied by the timpani. A last dash by the piano and orchestra leads to the concerto’s grand conclusion.

Classical, Concerto, Works

This is one of Haydn’s best-known concerti, and one of the most famous works for trumpet. Haydn composed it in 1796, and made full use of the solo ability of the chromatic trumpet, which had just come into its own.

The concerto is scored for large orchestra and displays the full panoply of Haydn’s mature orchestral style. An opening stately allegro gives the trumpet full reign to display melodic and technical prowess. The short slow movement features a beautiful opening melody in A-flat played by the strings and repeated by the trumpet, and displays an astonishing variety of harmonic invention.

The witty last movement, in rondo form with running passages by soloist and orchestra, closes out this work in dramatic style.

Concerto, Romantic, Works

The years from 1720 to 1750 were, from the perspective of the present, dominated by Johann Sebastian Bach; but for a musically aware person of the period Georg Philipp Telemann was the foremost musician of his day. His music, while firmly rooted in the contrapuntal intricacies of the Baroque style, served as a bridge between the old methods and the emerging Classical style of simple textures, clear harmonies, and elegant melodies.

Telemann founded the first series of public concerts, taking music from the spheres of court, church and opera house into the realm of audiences who wished to gather simply for the pleasure of listening. He saw that instrumental music in these other spheres was merely an adjunct to ceremony, contemplation or amusement, and that music could and should be appreciated as an abstract art, unadorned, and not subservient to other goals. His insight revealed a path that composers, performers, and audiences have trod ever since, leading directly to our concert today.

Although Telemann was the most prolific of 18th-century composers (a period when prolific composers abounded), he still found time to travel frequently and widely across Europe, absorbing musical influences from a wide variety of composers and nationalities. The “Concerto Polonois” was a result of a visit to Cracow, Poland, and it incorporates characteristic elements of Polish folk dance and presents them in the new compositional style.

Concerto, Romantic, Works

Schumann composed the ‘cello concerto in 1850, just before his third symphony and six years before his untimely death.

He styled it as a “Concert piece for ‘cello with orchestral accompaniment.” It is a three-movement work, although all of the movements are connected and played without break.

After three wind chords, the ‘cello opens with a soaring song-like melody, later echoed by the French Horn and by the winds after the slow movement. The short slow movement is a languorous interlude, featuring a simple solo melody accompanied by a solo orchestral ‘cello, string pizzicati and wind echoes. After a brief transition, with an evocation of the slow movement, the solo ‘cello leads into the quick last movement, which is characterized by a leaping two-note theme followed by rising sixteenth notes. The last-movement cadenza leads inexorably to a fast and joyous conclusion.

Baroque, Concerto, Works

Bach was a versatile composer. He reworked many of his instrumental concerti for harpsichord, and vice-versa (the two violin concerti, Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 and this concerto for oboe and violin are notable examples).

After considerable research, this three-movement work was reconstructed from Bach’s concerto for two harpsichords in C minor, the original violin-oboe version having been lost.

The first movement opens with an eighth-note theme with stated by the orchestra and answered by the violin and oboe. While the solo lines are prominent, they are interwoven with the orchestra, including delicate contrapuntal textures. The second movement is a lovely duet, with spun-out solo melodies juxtaposed against a muted, mostly plucked orchestral accompaniment. The vigorous last movement features sharp dynamic contrasts and florid solo passages before its resounding end.

20th Century, Concerto, Works

Strauss composed his elegant oboe concerto in exile in Switzerland shortly after the end of World War II.

A far cry from Strauss’ lush late romantic tone poems, the concerto harks back to the classicism of Mozart. Its themes are harmonically lucid and charming. The work is sparely scored for soloist and chamber orchestra (strings, woodwinds and horns).

The first movement is based on a recurring four-note motif in the strings, followed immediately by the soaring oboe melody and extensive thematic and harmonic development. The second movement, which follows without a break, includes an extended oboe cadenza accompanied in part by the orchestra. The sprightly third movement starts off with intertwined melodies involving the solo oboe, flute and clarinet. After a short cadenza, the main theme is transformed into a sweeping 6/8 closing Allegro.

Many of the motifs played by soloist and orchestra involve leaps and jumps reminiscent of other famous Strauss tone poems.

20th Century, Concerto, Works

The Russian contemporary of Honegger, Sergei Prokofiev grew up in the atmosphere of late Russian Romanticism that he abandoned as soon as his compositional style gained strength and individuality. His works already had very early on a motor, sometimes anti-emotional character, a tendency that Prokofiev, in the 1930s, would call “New Simplicity”—a rather theatrical, staged return to classic forms and means of expression different from Romanticized music.

After the Soviet revolution, Prokofiev in 1918 was granted an exit visa from the new Soviet government and went to Paris, where his 1st Violin Concerto received its premier. Although it had been difficult to find a soloist for the first concerto—many violinists “flatly refused to learn that music”—the 2nd Violin Concerto was commissioned by a group of admirers of the French violinist Robert Soëtans.

Written in 1935, shortly before his final return to his home country Russia (which he visited only briefly, having worked abroad since 1918), Prokofiev wrote: “The variety of places in which the concerto was written is a reflection of the nomadic concert-tour existence I led at that time: the principal theme of the first movement in Paris, the first theme of the second movement in Voronezh, the instrumentation was completed in Baku and the first performance was given in Madrid.”

Baroque, Concerto, Works

20th Century, Concerto, Works

Arthur Honegger’s lovely, neoclassical Concerto da Camera dates from 1948 and is scored for the unusual combination of flute, English horn (a larger version of the oboe), and strings. The first movement is like a gracious dialogue, the second a gravely beautiful song with wistful counterpoint and rich, dissonant harmonies. The finale is a rather lively dance, full of gentle good humor.

20th Century, Concerto, Works

No notes available.