Flower Duet from Lakmé: “Sous le dôme épais”

This enchanting duet is from Delibes’s famous 1883 opera. It is sung by Lakmé, the daughter of a Brahmin priest, and her servant Mallika, as they gather fragrant flowers by the river.

This enchanting duet is from Delibes’s famous 1883 opera. It is sung by Lakmé, the daughter of a Brahmin priest, and her servant Mallika, as they gather fragrant flowers by the river.

Schumann composed his Third Symphony in six weeks in 1850, after moving to the Rhineland to take up the post of music director in Düsseldorf. This symphony, which he premiered in 1851, quickly became one of his most popular works and is a masterpiece of romanticism.

Its five-movement structure is unusual, although not unique (both Beethoven and Berlioz had previously written multi-movement “programmatic” symphonies). The title “Rhenish” was not given by Schumann himself, but rather by his publisher. However, Schumann rejected a program idea for this symphony, believing that the music should be heard without the artifice of titles coming between the listener and the music, and he even removed some initial movement titles before publication. Despite this, glimpses of Rhenish life and influence can be easily discerned, especially in the second and fourth movements.

Structurally, this symphony can be viewed as having three sections – two thematically connected movements at the beginning and at the end, which bookend a lyrical “song without words” middle movement. The main theme is based on the interval of a falling fourth (E-flat to B-flat) followed by a rising sixth and rising fourth. These harmonic relationships are the basis for many of the themes in the other movements. The first movement begins with a theme propelled by rhythmic displacement, vigorously driving the piece forward. It is interrupted by a rising scale motive in the strings, which then leads to a lyrical second theme played by the woodwinds. All three themes become prominent and intertwined in the section. A triumphant return of the main theme is heralded by the horns and then taken up by the full orchestra at the end.

The second movement Scherzo is based on a German “ländler” folksong; like the first movement, it opens with a rising fourth in the ‘cellos, bassoons, and violas. After several variations, the Scherzo segues into a trio featuring horns and woodwinds. It reaches a climax, before ending in a hushed restatement of the main theme by the ‘cellos and first bassoon. The third movement is a tranquil musical miniature, akin to a song without words. Opening with a flowing theme by the clarinets and violas, it features a four-note motif in the strings imitated by other sections in the orchestra, which Schumann combines in the ending section.

The stately fourth movement is a magnificent example of Schumann’s inventiveness. It is marked “Feierlich” (solemnly), in the somber key of E-flat minor. Opening with trombones, horns and bassoons, the main theme is again based on a rising fourth. Schumann develops the opening theme in a remarkable overlapping and contrapuntal style, punctuated by brass fanfares towards the end of the movement. The last movement, “Lebhaft” (lively), is brisk and light-hearted. The opening theme again based on a rising fourth, this time in scale form. Towards the end of the piece, the brass – after yet another set of fanfares – return to the fourth movement theme, now in an optimistic tone. Brass flourishes and a quick coda propel this symphony to its triumphant ending.

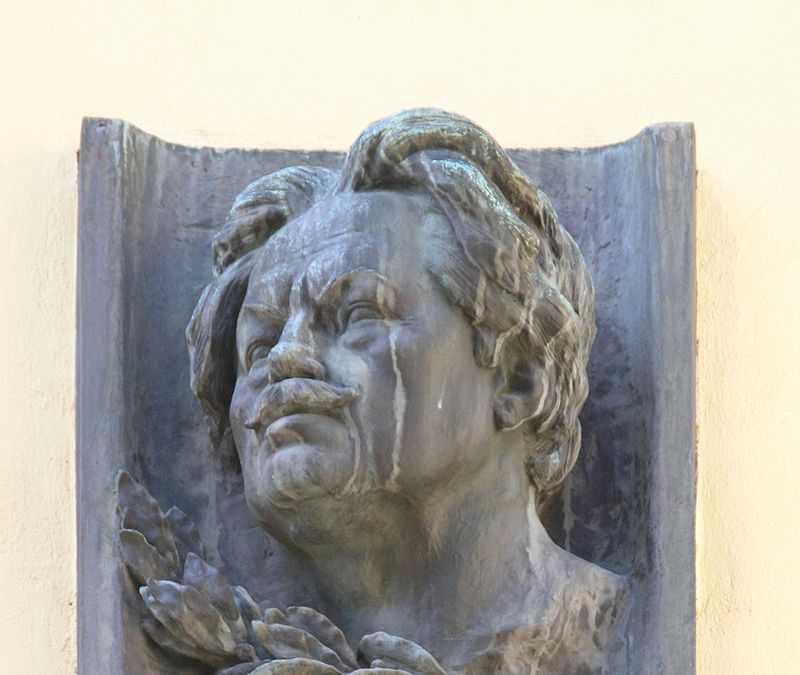

Grieg subtitle this lush work a “suite in the olden style.” He wrote it to commemorate the bicentenary of the birth of Ludvig Holberg (1684-1754), a celebrated writer, poet and dramatist claimed by both Denmark and Norway as a native son and dubbed “the Molière of the North.”

In evident homage to the baroque era in which Holberg lived, Grieg composed his suite in five short movements harking back to baroque form – a prelude followed by four short dance movements.

The “Praeludium” begins with rising scales punctuated by vigorous accents, with intermittent contrasting lyrical sections, and sets up the rest of the dances. The slow and stately Sarabande is introspective and tender, with short cello and violin solos. The elegant Gavotte follows with accented offbeats and a charming musette featuring string drones. The Air, marked “Andante religioso,” is the heart of the Suite. It is suffused with wistful melody and deeply-felt dialogues between solo cello and violins. The concluding Rigaudon is based on a jaunty French dance, which Grieg adapts to his own Norwegian folk style. Featuring a rollicking solo violin and viola duet in its main section, a short minor-key interlude leads to a joyous reprise to end the suite.

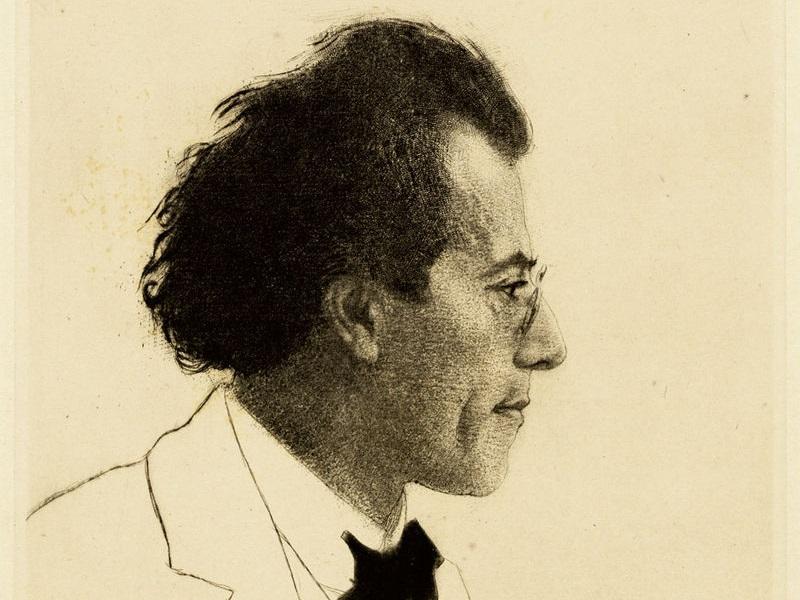

A very personal work, this song cycle by Mahler arose out of his unrequited love for a soprano he had met as a conductor in the Kassel opera house in the mid-1880s. Mahler wrote the text as well as the music, and both are deeply felt. He initially composed these songs for voice and piano, and then orchestrated them in the 1890s. There are four songs, which can be sung by either a mezzo-soprano or baritone.

I – “Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht” (“When My Sweetheart is Married”): He despairs on his beloved’s wedding day.

II – “Ging heut’ Morgen über’s Feld” (“I Went This Morning over the Field”): He finds joy in the midst of nature, birds and greenery. At the end, he questions whether he will ever find happiness.

III – “Ich hab’ ein glühend Messer” (“I Have a Gleaming Knife”): His unrequited love is like the agony of a sharp knife cutting into his chest. He imagines he sees his love’s blonde hair and blue eyes, and hears her laughter – and wishes he were lying dead, on a black bier.

IV – “Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz” (“The Two Blue Eyes of my Beloved”): Her blue eyes have sent him out into the wide world, away from everything he holds dear. He finds rest and sleep under a blooming linden tree by the side of the road. There everything was fine again – love and sorrow, world and dream.

Mahler used themes from two of these songs (nos. 2 and 4) in his Symphony #1.

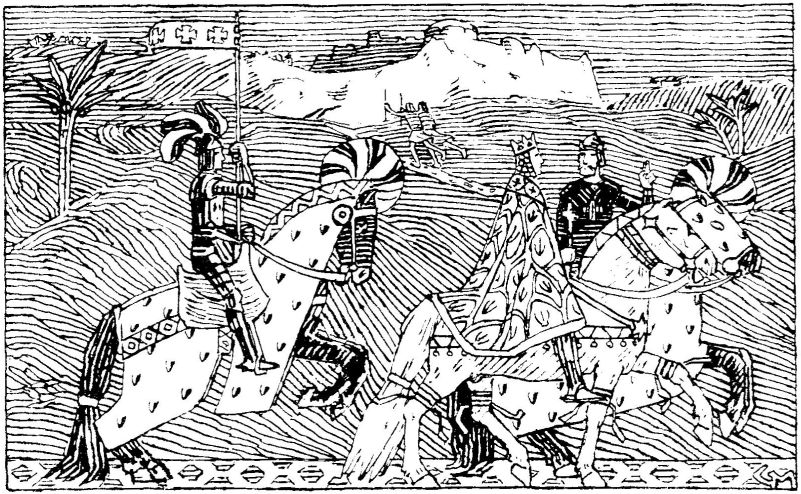

Grieg initially composed an eight-piece set of incidental music for a historical play written by his friend Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson. It was published as Op. 22 and first performed in Christiania in 1872. The play itself was based on the life of Sigurd Jorsalfar (“Sigurd the Crusader”), a king who ruled Norway from 1103-1130 and went on a crusade to Jerusalem. The plot focuses on the tensions between Sigurd and his brother/co-ruler Eystejn; a love-triangle of the brothers with Borghild; and the brothers’ reconciliation. In later years Grieg compiled a 3-movement orchestral suite based on the original incidental music. He published it as Op. 56, and it was premiered in Oslo in 1892.

The opening prelude, “In the King’s Hall,” is a graceful march, first stated in the winds and then taken up by the entire orchestra. A contrasting lyrical section featuring woodwinds leads to a reprise of the opening section. The Intermezzo (“Borghild’s Dream”) is dark and mysterious, with a contrasting agitated section punctuated by string and wind outbursts. The final “Homage March,” originally meant to signify the brothers’ reconciliation, opens with brass fanfares. The main martial theme is played first by four solo ‘cellos, and then broadened to include strings, solo winds, and brass. A contrasting middle section is introduced by percussion and harp and features the strings. The martial theme is repeated by the orchestra to end the Suite.

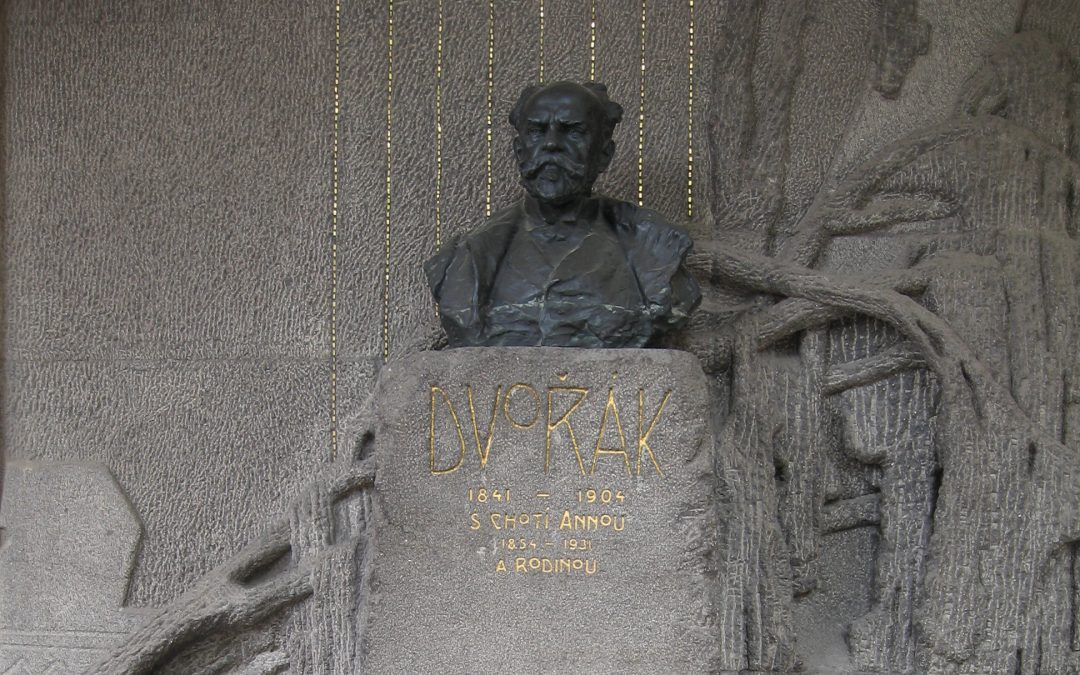

Dvořák composed his violin concerto, a masterpiece of the romantic concerto literature, in 1879. He was inspired to write it after meeting the great violinist Joseph Joachim, to whom he had been introduced by Johannes Brahms. Dvořák sent the initial manuscript to Joachim, who suggested a number of changes to it, particularly in the solo part, and Dvořák subsequently revised it. However, Joachim never performed the concerto, possibly on account of its unorthodox structure. After a number of other revisions, the concerto was premiered in Prague in 1883, with the noted young Czech violin virtuoso František Ondříček as the soloist.

With lush melodies and allusions to Czech folk tunes, the violin concerto fits squarely into Dvořák’s “Slavic” period, during which he composed works such as his 6th Symphony, the Czech Suite, the first set of Slavonic Dances, the E-flat Major String Quartet Op. 51, and the A-Major String Sextet Op. 48.

The concerto is a three-movement work, albeit with some unusual features. It opens with a vigorous orchestral “foreshadowing” theme in A minor; the passionate main theme is introduced by the solo violin a few bars later. A gentle second theme in C Major appears in the middle of the movement. The music then becomes more free-form, taking on an almost a rhapsodic quality. After a restatement of the opening theme, instead of a full recapitulation there is a short transition section featuring solo violin and woodwinds, and the music then moves without a break into the second movement.

The lyrical Adagio is an extended meditation on a free-flowing theme. It is interrupted several times by an abrupt dialogue between the solo violin and horns, later taken up by the full orchestra. The end of the movement features a novel duet between the solo violin and horns before ending in a reverent hush.

The lilting third movement is full of folk-theme references. It opens with an uplifting theme based on the furiant, a spritely Czech dance. In the middle of the movement, a slower section based on the Czech dumka makes its appearance. A final statement of the opening furiant brings the concerto to a joyous close.

Mahler composed this intense and dramatic piece in 1888, just after he had finished composing his Symphony No. 1 (the “Titan”). Originally composed as a tone poem, Mahler incorporated it, with a number of changes, seven years later into his massive Second Symphony (the “Resurrection”). Mahler himself, a noted conductor as well as composer, performed “Totenfeier” as a standalone piece in a number of concerts, even after finishing his Second Symphony.

A number of Mahler’s writings indicate that he thought of this work as the finale to his first symphony — that he was in fact burying the hero of the “Titan.” The tone poem is structured as a funeral march, but is also interspersed with ethereal interludes and themes of menace and terror. In the middle of the movement, the brass section introduces the “Dies Irae”, a medieval Latin hymn referring to Judgment Day. Of note, Mahler did write program notes for his Second Symphony in 1901, but later withdrew them from publication. They nonetheless open a window for us into his thinking. Here is how he described “Totenfeier:”

We are standing at the coffin of a well-loved man. His life, struggles, suffering, and passions pass by our mind’s eye for the last time. — And now, in this solemn and most shattering moment, when the confusions and distractions of everyday life are stripped away, a terrible grim voice, which we usually ignore in life’s daily hustle and bustle, grips at our heart: Now what? What is this life — and this death? Does it continue for us? Is it all just an empty dream, or does this life and this death have a purpose? — And we must answer this question, if we are to continue living.

In the silence of the sandy steppes of Central Asia, the sounds of an unfamiliar peaceful Russian song are heard. In the distance we also hear the melancholy sounds of an oriental melody, and the steps of approaching horses and camels; a caravan approaches. Under the protection of Russian soldiers, the caravan continues its long journey securely and without fear on its way through the immense desert. The Russian and Asiatic melodies join in a common harmony; their refrains continue to be heard for a long time before finally dying away in the distance.

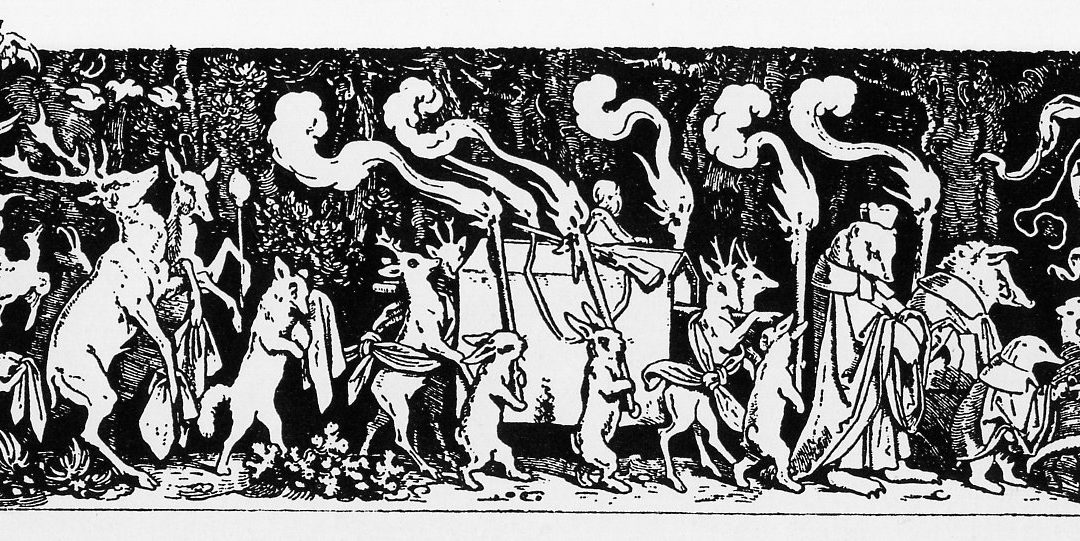

Mussorgsky was a member of an influential group of Russian composers known as “The Five” – Mily Balakirev, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Borodin. Together they forged a uniquely Russian musical style based on the country’s folklore and history. Mussorgsky himself composed numerous works for piano, orchestra, opera and voice. Among his best-known works are the opera Boris Godunov, the orchestral tone poem Night on Bald Mountain, and the piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition.

The piano suite was composed in 1874 and was based on a series of drawings and paintings by the Russian artist Viktor Hartmann. It proved so popular that numerous arrangements have been made of it (the Ravel orchestration done in 1922 is the best-known of these). The first orchestration of Pictures at an Exhibition, which we are performing at this concert, was prepared in 1886 by Mikhail Tushmalov, a pupil of Rimsky-Korsakov. Rimsky himself oversaw the editing of the score and conducted the première, in 1891.

This orchestral arrangement contains most of the original movements of the piano suite. After the opening Promenade, the mood shifts to the “Old Castle,” with haunting melodies introduced by bass clarinet and English horn. Next is the spritely “Ballet of the Chicks in their Shells” featuring strings and woodwinds; “Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle” is a ponderous dialogue between two Polish Jews, one rich and the other poor. “Market at Limoges” depicts women arguing furiously in a small French town marketplace. The tone shifts abruptly in “Catacombs;” punctuated by sudden brass chords, it is based on a painting in which Hartmann is examining the famous underground catacombs of Paris by lantern light. In the following “Con mortuis in lingua mortua,” the opening “Promenade” theme is eerily reprised in a minor key. The “Hut on Hen’s Legs” is based on a Hartmann drawing of a clock in the form of a witch’s hut; Mussorgsky puts the focus on the witch’s flight, with dramatic scales and passages in thirds.

It leads directly to the grand last movement, “The Great Gate of Kiev”. It is based on Hartmann’s design of a monumental gateway to the city in an ancient massive Russian style, capped with a cupola shaped like a Slavonic helmet. Its familiar grand theme is repeated several times with increasing intensity, interspersed with wind interludes reminiscent of Russian Orthodox chants. It ends in a triumphal paroxysm of massive chords and pealing bells.

Dvořák’s masterful Sixth Symphony is at once a sunny, lyrical work with moments of great subtlety, power and magnificence.

It was written in 1880, only three years after Brahms’ Second Symphony, to which it has certain similarities in choice of keys and orchestration. That being said, this is Dvořák’s first “mature” symphony, written in the “Slavic” style that characterizes his other orchestral and chamber works of that period. The Sixth Symphony was premiered in Prague in 1881 and soon became a staple of the orchestral repertoire.

Dvořák incorporates Czech folk melodies throughout, in particular in the famous “Furiant” third movement, based on a Czech dance. The first movement starts on a serene and sunny note, evoking the Bohemian countryside; a vigorous outburst by the horns and violins leads to majestic restatement of the main theme by the entire orchestra. A lyrical second theme is heralded by the oboe; both themes are thoroughly developed and interwoven throughout the entire orchestra. The second movement is a sweet nocturne, with counter-themes tossed back and forth between strings, winds and brass.

The Furiant is all about energy and syncopation, evoking Dvořák’s iconic Slavonic Dances. After a calm and melodious trio section, the Furiant returns in full force. The last movement starts out innocently enough in the strings, with a playful second triplet-based theme, before its massive development in the winds and brass. A stirring rendition of the main theme in slow motion, featuring the full-throated brass section, heralds the triumphant finale.